THOMSON, Daniel Alexander Edward (#845352)

Daniel Alexander Edward Thomson suffered a fate that too many soldiers in The Great War experienced. After enlisting in 1915, Daniel was deployed overseas, but did not arrive in France until early in 1918. Several months later, he was embroiled in a pivotal campaign, one that featured intense and brutal fighting as the end of the war neared. Private Daniel Thomson Jr. was killed in action in the second offensive of this final campaign.

Daniel Thomson was born in Alvinston, Ontario, on June 24, 1894, the youngest son of Daniel Sr. (a carpenter, born about 1858) and Ellen (nee Gunn) Thomson, who was 12 years her husband’s junior. After getting married on January 6, 1891, in Alvinston, Daniel, 33, and Ellen, 21, spent some time in Dawn Township before moving to 338 Cameron Street in Sarnia. They were blessed with five children: Alvin Ernest (born April 10, 1891); William James Connell (born September 15, 1892, passed away at the age of 11 on October 23, 1903 due to diptheria); Daniel Alexander Edward (born 1894): Mary Margaret (born September 2, 1896); and Kathleen (born August 21, 1898).

Tragedy struck the Thomson family in March 1899 when Daniel Sr. passed away. At the time, Daniel Jr. was only four years old, and their daughter Kathleen was only seven months old.

Ellen Thomson remarried on December 30, 1902, to Lawrence “Larry” Roberts, a labourer in Kent County. Ellen and Larry had three daughters together—stepsisters for Daniel and his siblings: Katherine “Katie” Elizabeth (born March 18, 1905); Annie Violet (born June 14, 1908); and Velma (born February 10, 1911). In 1911, the Thomson/Roberts family was residing together at 458 George Street, Sarnia. Living Larry and Ellen Roberts were their children: Alvin (age 20, employed as a machinist, along with Alvin’s wife Fyrne Levina); Daniel Jr. (age 16, employed with the railroad); Mary (age 14); and Kathleen (age 12) Thomson; and Katie (age 6); Annie (age 3); and Velma (age 8-months) Roberts.

Daniel’s older brother, Alvin Ernest Thomson, 24, also enlisted in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary

Force in Sarnia, on December 22, 1915. He did so two weeks after Daniel Jr., had enlisted. Employed as a machinist, Alvin was residing at 276 Maria Street at the time, with his wife Fyrne Levina Thomson, who he recorded as his next-of-kin. Alvin, like his brother, became a member of the Lambton 149th Battalion.

Nine months later, Alvin was discharged, the result of being A.W.L. Three months later, on December 27, 1916, Alvin enlisted again with the 149th Battalion in London, Ontario. Alvin and Fyrne were residing at 196 Penrose Street in Sarnia at the time. Unfortunately, for Private Alvin Thomson, he never had the opportunity to serve overseas. Two months after his second enlistment, on February 9, 1917, he was struck off strength from the 149th Battalion, declared as medically unfit for service (his index and middle finger of his left hand were missing, lost in a corn shredder accident).

Daniel Alexander Edward Thomson, 21, enlisted in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force (CEF) on December 7, 1915, in Sarnia, two weeks before his older brother Alvin enlisted. Daniel stood five feet eight inches tall, had blue eyes and brown hair, was single, and recorded his present address as Sarnia, Ontario. He also recorded his trade or calling as labourer, and his next-of-kin as his mother, Ellen Roberts, who was residing in Dawn (R.R. #2, Sarnia), Ontario. Her address was later changed to 252 Shamrock Street, Sarnia.

Daniel became a member of the 149th Battalion, Western Ontario Regiment, CEF, and during his initial training, he was injured a couple of times. On July 22, 1916, he sprained his ankle and was admitted to the hospital at Camp Borden. He was discharged three days later. On November 7, 1916, he was promoted to the rank of lance corporal. On January 22, 1917, he was admitted to the Military Hospital in London, the result of a sprained wrist and injury to his hand. After having a splint applied and with his injuries improving, he was discharged from the hospital on January 30, 1917.

Approximately 15 months after enlisting, on March 25, 1917, Daniel Thomson Jr. embarked overseas from Halifax bound for the United Kingdom aboard S.S. Lapland. He arrived in Liverpool on April 7, 1917, and from the Segregation Camp, was transferred to the 25th Reserve Battalion, CEF, at Bramshott. Less than two months later, on June 1, 1917, he was taken on strength into the 161st Canadian Infantry Battalion at Camp Witley. Eight months later, on February 28, 1918, Private Daniel Thomson Jr. proceeded from Camp Witley and arrived in France where he became a member of the Canadian Infantry, 47th Battalion, British Columbia Regiment.

Early in the summer of 1918, Allied Commanders proposed a plan to take advantage of German disarray following their failed Spring Offensive. Canadian troops were to play a key role as “shock troops” in cracking the German defences. They spent two months preparing for what became their Hundred Days Campaign.

Approximately five months after arriving in France, Daniel was taking part in this campaign. The Hundred Days Campaign (August 8 – November 11, 1918, in France and Belgium) was the “beginning of the end” of the Great War. Canadians were called on again and again over the three-month period to lead the offensives against the toughest German defences. The series of victories repeatedly drove the Germans back, culminating in Germany’s unconditional surrender on November 11, but it came at a high price: approximately 46,000 Canadians were killed, wounded, or missing.

The first offensive in the Campaign was the Battle of Amiens in France (August 8-14, 1918), a truly all-arms battle, one in which all four Canadian divisions were involved. Over the course of one week, in a battle that British Field Marshal Douglas Haig called “the finest operation of the war”, the Canadians would advance nearly 14 kms—but it came at a cost of 11,822 Canadian casualties.

The second offensive in the Campaign was the Battle of Arras and Breaking the DQ Line in France (August 26-September 3, 1918), where Canadians were part of a spearhead force tasked with crashing one of the most heavily fortified positions, the Hindenburg Line—a series of strong defensive trenches and fortified villages. General Sir Julian Byng called the Canadian victory at the 2nd Battle of Arras and breaking of the DQ Line “the turning point of the campaign”, but it came at a cost of 11,400 Canadian casualties.

The DQ (Drocourt-Queant) Line was the very heart of the German defence system in this area of France—the Germans had spent two years building this heavily fortified and well-defended barrier. The assault began on September 2 at 4:50 a.m. with Canadian troops leaping from their forward trenches and moving forward closely behind a massive creeping barrage. Against nearly unimaginable odds, bombed mercilessly by enemy shellfire, and raked by machine guns, the battered Canadians advanced through two days of intense fighting, and succeeded in breaking the DQ Line. Some military experts called the attack on this objective the hardest single battle of the war for the Canadian Corps.

On September 3, 1918, during this brutal offensive on the DQ Line, Private Daniel Thomson Jr. of the 47th Battalion, was killed in action. His body was never recovered. He was simply recorded as the following: Date of Casualty: 3-9-18. Killed in Action.

Shortly after Daniel was killed in action, communication from the military about his death was sent to his mother, Mrs. Ellen Roberts c/o Mr. George Pilkey, R.R. #1 (12th Line), Corunna, Ontario.

Twenty-four-year-old Daniel Thomson Jr. has no known grave. He is memorialized on the Vimy Memorial, Pas de Calais, France.

Source: The Sarnia War Remembrance Project by Tom Slater

Editors: Tom St. Amand and Lou Giancarlo

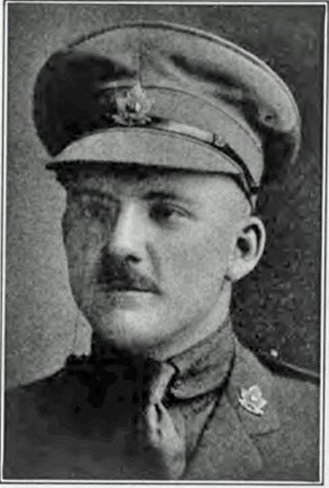

TIMPSON, Edward Arthur (#602317)

Edward Arthur Timpson emigrated from England and found work as a florist in Sarnia, where he enlisted at age 21. At the front lines, he survived momentous battles at the Somme, Vimy Ridge, Lens and Hill 70, and Passchendaele. During a major offensive in the last great campaign of the war, he was fatally wounded when he was hit by enemy shellfire.

Edward Arthur Timpson was born in Great King’s Hill, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, England, on August 25, 1893, the son of Edward Osborne and Hester Augusta (nee Fulford) Timpson, both of Great King’s Hill, England.

NOTE: This birthdate is based on what Edward recorded on his Attestation Paper when he enlisted. Therefore, in his military Personnel Records, his age at enlistment and age at death are based on this birthdate; however, in both the 1901 and 1911 England and Wales Census records, Edward’s birth year is recorded as 1897. The England and Wales Civil Registration Birth Index record his birthdate as sometime in October-November-December 1896. [These records also list his first name as Edwin vs. Edward. Throughout his military Personnel Records, he signed his first name as Edward]. Based on the England/Wales census and birth index, it is possible that Edward Timpson lied about his age at enlistment. He may have been three or four years younger than the age he recorded.

On December 19, 1880, Edward Osborne Timpson, born 1856 in Buckinghamshire, England, married Hester Augusta Fulford of Hertfordshire, England, who was also born in 1856. The marriage took place at St. James in Paddington, Westminister, England, and, over the years, Edward Sr. and Hester were blessed with 10 children together: Charles Edward (born 1881); Mary Augusta (born 1883); Claritta Elizabeth Ellen (born 1884); Lilian Eliza (born 1886); Frank (born 1888); Harry Osborne (born 1890); Lucy Alice (born 1892); William Herbert (born 1894); Edward Arthur (born 1893 or 1897); and Isabel Elizabeth (born 1899).

In 1891, the Timpson household included parents Edward Sr. and Hester and their six children: Charles Edward, Mary Augusta, Claritta, Lilian Eliza, Frank and Harry Osborne Timpson. In 1901, the Timpson family was residing in Great King’s Hill where Edward Sr. supported his family as a carpenter and nine children lived with them: Charles Edward (a carpenter), Lilian Eliza, Frank, Harry Osborne, Lucy Alice, William Herbert, Edwin Arthur (age 4), and Isabel Elizabeth. Ten years later, in 1911, most members of the Timpson family were still residing together in Great King’s Hill, England—parents Edward Sr. (a carpenter) and Hester and their five children: Frank (age 23, an upholsterer); Harry Osborne (age 21, a grocer); William Herbert (age 16, a baker); Edwin Arthur (age 14); and Isabel Elizabeth (age 11), and a granddaughter Gertrude Clarrita Timpson (age 8).

Older brother Charles Edward Timpson, who married in 1905, immigrated to Canada in 1913, along with his wife Elizabeth (nee Shorey) and their three children at the time: Ena Myrtle, Stanley Frederick and George Edward. Charles and Elizabeth Timpson resided at 178 Penrose Street, Sarnia, and Charles supported his family by working as a carpenter. Charles and Elizabeth had two more children together: Margaret and Jean Timpson.

Edward Arthur Timpson immigrated to Canada the year after his older brother Charles. Edward departed from Southampton, England, and Cobh, Ireland, aboard S.S. Andania and arrived in the port of Quebec on May 10, 1914. He was recorded as 19 years old, his intended destination as Sarnia, his former occupation as gardener, and his intended occupation as fruit farmer.

Prior to enlisting, Edward was employed by A. Macklin, florist, in Sarnia. In 1915, both Charles and Edward Timpson were residing at 295 Mitton St., N. Twenty-one-year-old Edward Timpson enlisted in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force (CEF) on January 14, 1915 in Sarnia. He stood six feet and one inch tall, had hazel eyes and black hair, was single, and recorded his trade or calling as gardener, and his next-of-kin as his father, Edward Timpson Sr., of Great King’s Hill, Buckinghamshire, England. Edward Timpson became a member of the 34th Battalion, CEF.

Nine months after enlisting, on October 23, 1915, Private Edward Timpson embarked overseas bound for the United Kingdom aboard S.S. California. He arrived in England on November 1, 1915, and was initially stationed at Camp Bramshott. Three months later, on February 3, 1916, he was transferred to the 23rd Battalion, stationed at West Sandling, and three weeks after that, on February 26, he was promoted to acting corporal.

Three months later, on May 25, 1916, Edward reverted to the rank of private on his request and was transferred to the 2nd Battalion. The next day, May 26, Private Edward Timpson arrived in France, where he was taken on strength into the 10th Battalion, Alberta Regiment. He departed the Canadian Base Depot in France on June 6, 1916, where he joined the 10th Battalion in the field the next day. Nine days later, on June 16, 1916, Edward was promoted in the field to lance corporal in the 10th Battalion.

For more than a year-and-a-half after Timpson joined this unit, as part of the 1st Canadian Division, the 10th Battalion took part in many of the significant battles involving the Canadian Corps in France and Belgium. This included the Battle of the Somme (July 1-November 18, 1916)—one of the bloodiest and most futile battles in history; the Battle of Vimy Ridge (April 9-12, 1917)—the first time (and last time in the war) that all four divisions of the Canadian Corps, with soldiers from every region in the country, surged forward simultaneously; the Attack on Hill 70 and Lens (August 15-25, 1917)—where they faced enemy flame-throwers and mustard gas for the first time; and the Battle of Passchendaele (October 26 – November 10, 1917)—one waged in unceasing rain on a battlefield that was a nightmarish mess of rotting, mangled corpses, gagging gas, water-filled craters, and glutinous mud.

Miraculously, Edward Timpson survived these momentous battles, and on two occasions during that time, he was promoted in rank: on August 22, 1917, he was appointed acting corporal, and less than two months after that, on October 10, 1917, he was promoted to corporal in the 10th Battalion.

Early in the summer of 1918, Allied Commanders proposed a plan to take advantage of German disarray following their failed Spring Offensive. Canadian troops were to play a key role as “shock troops” in cracking the German defences. They spent two months preparing for what became their final great campaign of the war. Edward was soon embroiled in this campaign, one that featured intense and brutal fighting as the end of the war neared.

The Hundred Days Campaign (August 8 – November 11, 1918, in France and Belgium) was the “beginning of the end” of the Great War. Canadians were called on again and again over the three-month period to lead the offensives against the toughest German defences. The series of victories repeatedly drove the Germans back, culminating in Germany’s unconditional surrender on November 11, but it came at a high price: approximately 46,000 Canadians were killed, wounded, or missing.

The first offensive in the Campaign was the Battle of Amiens in France (August 8-14, 1918), a truly all-arms battle, one in which all four Canadian divisions were involved. Over the course of one week, in a battle that British Field Marshal Douglas Haig called “the finest operation of the war”, the Canadians would advance nearly 14 kms—but it came at a cost of 11,822 Canadian casualties.

On August 15, 1918, ten days before his 25th birthday, Corporal Edward Timpson was wounded in action—hit by enemy shellfire, during the final days of the Battle of Amiens. He was taken to No. 47 Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) where his wounds were recorded as “SW (shell or shrapnel wound) penet. Abdomen and SW hand and leg right and neck.” Later that day, Corporal Edward Timpson passed away as a result of his wounds at No. 47 Casualty Clearing Station. Edward’s Commonwealth War Graves Register records him as Date of Death: 15-8-18. Died of Wounds – No. 47 Casualty Clearing Station. S.W. Penet abdomen etc…

Edward’s remains were buried in Dury Hospital Military Cemetery, ¾ miles South of Amiens, and later exhumed and reburied at Villers-Bretonneux Military Cemetery.

In mid-September 1918, Charles, still residing at 142 Penrose Street, received the news of his brother’s death. Edward was the second Timpson son to lose his life in the war. Three years prior to Edward’s death, his brother William Herbert Timpson, had been killed in action with the British Army in Flanders. Private William Herbert Timpson, of the 10th (Service) Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment, was killed in action on September 25th, 1915.

A third brother, Harry Osborne Timpson, had also enlisted with the British Army when the war broke out. Harry Timpson survived the war. It is worth noting that Edward’s mother, Hester Augusta Timpson, and her sister, Mrs. Nash, both residing in England, had ten sons in their families, eight of whom enlisted. Of the three Timpson boys who enlisted, two lost their lives in war—Edward Arthur and William Herbert.

Edward Arthur Timpson, 24, is buried in Villers-Bretonneux Military Cemetery, Somme, France, Grave VI.AA.10.

Source: The Sarnia War Remembrance Project by Tom Slater

Editors: Tom St. Amand and Lou Giancarlo

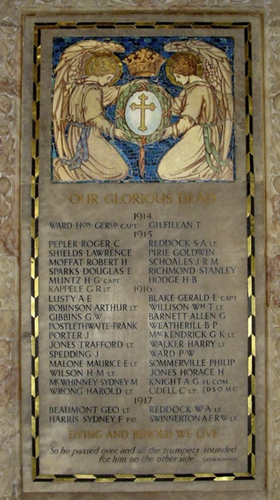

TOWERS, Norman Ewart

Sarnia-born Norman Ewart Towers had been practicing law for four years when he enlisted in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force (CEF) in April 1915. Seven months later, he arrived in France and rose to the rank of captain. During a major offensive in the atrocious Battle of the Somme, where mass butchery was the precedent, Norman Towers was fatally wounded. It had been only 17 months since he had enlisted.

Norman Towers was born in Sarnia, Ontario, on October 7, 1887, the youngest son of Thomas Foard and

Mary Ann (nee Huggart) Towers. Thomas Foard Towers, born November 1845, in Airth, Stirlingshire, Scotland, emigrated from Scotland with his family in 1856. Sixteen years later, on September 17, 1873, 27-year-old Thomas married 27-year-old Mary Ann Huggart (who was born July 1846, Durham, Ontario) in Putnamville, North Dorchester, Middlesex, Ontario.

By 1875, Thomas and Mary Ann Towers were residing in Sarnia, and eventually at 231 College Avenue, N., where they raised six sons together: Alfred St. Clair (born April 21, 1875); Robert Irwin (born October 29, 1876); James Crawford (born November 17, 1879, passed away on November 15, 1910 due to carcinoma of liver, leaving behind his wife Florence and their 7-month old son James); Gordon King (born June 18, 1881); Thomas Logan (born July 15, 1884) and Norman Ewart (born 1887). Over the years, Thomas Towers supported his family by working at a number of occupations, including being a bookkeeper, a clerk, an accountant, and a hardware merchant. In 1895, Thomas was a member of the Lambton 27th Battalion, St. Clair Borderers, along with his 19-year-old son Robert.

In 1891, the Towers household in Sarnia included parents Thomas (a book keeper) and Mary Ann, along with their children: Alfred (a bank clerk), Robert, James, Gordon, Thomas and four-year-old Norman Ewart, along with 70-year-old Agnes Towers, the mother of Thomas. Ten years later, in 1901, the Towers household included parents Thomas (an accountant) and Mary Ann, along with their children: Robert (a barrister), James (an assistant bookkeeper), Thomas, and 13-year-old Norman Ewart, along with their general servant, 22-year-old Mary Toban.

Two of Norman’s brothers, Robert Irwin and Thomas Logan, also served overseas during the Great War. Thirty-eight-year-old Robert Irwin, a barrister at law, enlisted on September 14, 1915, in London, Ontario. Robert completed his Officers’ Declaration Paper soon after and was appointed Lieutenant-Colonel with the 70th Battalion, CEF. In April 1916, he embarked overseas from Halifax bound for the United Kingdom. In England, he was appointed a member of the Board for adjustment of Regimental Funds. In February 1917, Robert was appointed President of Regiment Funds Board. He returned to Canada in May 1917. Robert Towers was discharged from service and struck off strength in October 1917.

Thirty-year-old Thomas Logan, a physician, enlisted in Guelph in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force on January 25, 1915. Initially, Thomas was appointed the medical officer of the 108th Regiment with the rank of lieutenant. In June 1915, he embarked overseas, and once in England, was taken on strength into the Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC). He was appointed captain, and was initially attached to the Canadian Convalescent Hospital, Monks, Horton. On July 6, 1916, the then Major Thomas Towers arrived in France, as a member of the CAMC. He served in a number of general hospitals and Canadian field ambulance units in France. Thomas Towers survived the war and was struck off strength on general demobilization in May 1919.

Norman Ewart Towers was educated at Sarnia’s public and high school and then attended the University of Toronto, first receiving his Bachelor of Arts (Political Science) 1905-08 degree, followed by his law degree in 1911. Norman became a barrister and practiced law in Port Arthur, Ontario, with the firm of Keefer, Keefer & Towers.

Twenty-seven-year-old Norman Towers enlisted in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force (CEF) on April 15, 1915, in Port Arthur, Ontario (he completed a second Attestation Paper on April 30, 1915). Norman stood five feet seven inches tall, had blue eyes and brown hair, was single, and was employed as a “barrister-at-law”. He

recorded that he was a member of the Active Militia, the 96th Lake Superior Regiment, and that he had four years prior military experience in the 1st Hussars, Canada. He also recorded his next-of-kin as his father, Thomas F. Towers, of Sarnia. Norman became a member of the Army, 52nd Reserve Battalion, CEF. Just prior to going overseas, Norman returned to Sarnia to visit his parents, family, and friends.

On June 17, 1915, Norman embarked overseas from Montreal bound for the United Kingdom aboard S.S. Scandinavian with a special draft of 250 men from 52nd Battalion. On June 29, 1915, in England, he was transferred to the 32nd Reserve Battalion, CEF. One month later, on July 29, 1915, Lieutenant Norman Towers’ April 15, 1915 Attestation Paper was certified by a magistrate, and his Certificate of Medical Examination was signed at Shorncliffe Camp, England. Two months later, on September 23, 1915, he was transferred to the Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR). Five weeks later, on November 1, 1915, Lieutenant Norman Towers arrived in Boulogne, France, with the RCRs.

On November 15, 1915, Norman wrote a letter from France to his parents Thomas and Mary Ann in Sarnia. The following is a portion of that letter:

Dear Father,

I presume that by now mother will have received my letter and also post card. At present we are comfortably settled at billets. Each company billets by itself and there are seven of us in one room no larger than our sitting room at home and there we eat, and sleep and live, and also do our own cooking, but it is surprising what one can get used to when you try, and it is warm at night, which is a big consideration. Yesterday we saw a wonderful sight, aeroplanes dodging the anti-aircraft guns and on a tremendous scale it reminds one of trying to shoot hawks at a great height.

This country is an awfully pretty one, more so than England, and is just like the pictures one sees – particularly the long rows of tall trees laid in absolutely straight lines. Naturally, I can’t tell you anything of our position or movements, etc., but as yet we have not been in the front trenches, though we may be soon. Persistent rumors of peace negotiations are circulating, but I daresay you people at home know more about that than we do. The mail service is excellent and last night I got yours and mothers letters, and some others… I was the most envied man in the company that night, for letters are the main thing over here.

I find that I have brought over practically everything that I need, although my boots have shrunk a bit with the continued wet and I have come to the conclusion that the only way to do it is to buy boots at least two sizes too large – they are one of the main troubles over here, as there is lots of marching to do. In spots the mud is fearful, but nothing to what it would be if this war were round Oil Springs. Do you remember some of our trips out there and in particular the one when you and I and Rob and mother got lost coming home at night – it is still fresh in my memory.

Where we are just now, although the enemy were at one time in possession of it, there are no signs of war. Perriman and I were out for a walk today and it was just like one at home in the country. We both wished it might have been. From now on my letters will have to be shorter as the opportunities for them are few and as a rule we are dog-tired. I am enjoying the life immensely and will continue to do so for a time anyway – every moment there is something new. Be sure to write often as letters are doubly welcome now, and even if I only send a card, it will serve

to let you know that I am well and going. Much love as ever, to you both, and you are constantly in my thoughts, as I am sure I am in yours.

Yours lovingly, Ewart

Lt. N.E. Towers, “D” Company, R.C.R. Canadian Corps

Four months after writing the above letter, on March 13, 1916, Norman became a member of the 7th Canadian Light Trench Mortar Battery. Three months after that, on June 14, 1916, he was promoted to temporary captain, in command of the 7th Canadian Light Trench Mortar Battery.

Norman Towers was soon immersed in the gruesome fighting of the Battle of the Somme. Waged from July 1-November 18, 1916, it was one of the most futile and bloody battles in history. The Somme, a battle of attrition, lasted for more than four brutal months and saw the Allies advance around 10 kilometers. A more telling statistic is the number of injuries and deaths: of the 85,000 Canadian Corps, there were more than 24,000 Canadian casualties.

The second major offensive of the Somme battle was the week-long Battle of Flers-Courcelette (September 15-22). It was here where tanks made their first appearance in the war. The Battle was a stunning success for the Canadians, but it came at a cost of over 7,200 casualties. It was during this second major offensive of the Somme battle where Norman Towers was killed in action.

On September 19, 1916, three months after being promoted, Captain Norman Towers of the 7th Canadian Light Trench Mortar Battery was wounded in action during the Battle of Flers-Courcelette—he was hit multiple times by enemy gunfire. A Medical Case Sheet recorded that “Lieutenant Norman Towers of the RCR… was admitted to No. 2 Red Cross Hospital, Rouen, at about 4:00 a.m. on September 19, 1916”. Also on the Medical Case Sheet, the doctor recorded that Towers had “GSW Multiple” and “was suffering with multiple wounds involving scrotum and penis, right thigh and buttock, and left thigh”, and “On admission he was very collapsed and there were signs of ‘gas’ infection of the thighs”. Norman Towers was operated on by two doctors that morning at 9:30 a.m., where one doctor recorded, “shell fragments were removed from both thighs and gas gangrene present.”

The next day, on September 20, at No. 2 Red Cross Hospital, Rouen, Norman Towers was recorded as “GSW (gun-shot wound) buttock, dangerously ill”. Later the doctor added to Norman Towers Medical Case Sheet that “The patient never rallied & never became quite conscious & died at 1 A.M. Sept 20, 1916”.

Norman Towers’ Commonwealth War Graves Register records him as Date of Death: 20-9-16. Died of Wounds No. 2 Red Cross Hospital, Rouen.

On September 20, 1916, Norman’s parents in Sarnia received two telegrams, both from the official war records office in Ottawa. The two official telegrams read as follows:

Thos. F. Towers, Sarnia, Ont.

Sincerely regret to inform you Captain Norman Ewart Towers, artillery, officially reported dangerously ill at Red Cross Hospital, Rouen, Sept. 20th. Gunshot wounds. Will send further particulars when received.

Signed, Officer in Charge, Record Office.

and

Thos. F. Towers, Sarnia, Ont.

Deeply regret to inform you Captain Norman Ewart Towers, artillery, officially reported died of wounds, Sept. 20 at No. 2 Red Cross Hospital, Rouen. Signed, O.I.C.R.O.

Sarnians learned of the death of Norman Towers in the September 22, 1916, edition of the Sarnia Observer. The front-page headline read Two Sarnia Young Men Make Supreme Sacrifice (Sarnians also learned that Lance Corporal Robert Palmer Crawford had died of wounds eight days earlier – Robert Crawford’s story is also included in this Project).

Twenty-nine-year-old Norman Towers is buried in St. Sever Cemetery, Rouen, Seine-Maritime, France, Grave Officers, A.101.5. On his headstone are inscribed the words BORN IN SARNIA, CANADA.

His name is also inscribed on the First World War Memorial in Osgoode Hall’s Great Library, Toronto. The Osgoode Hall memorial contains the names of law students and graduates who died as a result of the war.

There is also a memorial stone in Lakeview Cemetery in Sarnia. Inscribed on it are these words: 1887-1916 CAPT. N.E. TOWERS O.C. 7TH CAN. T.M.B. FELL AT COURCELETTE FRANCE SEPT. 16, 1916 FAITHFUL UNTO DEATH I WILL GIVE THEE A CROWN OF LIFE.

Source: The Sarnia War Remembrance Project by Tom Slater

Editors: Tom St. Amand and Lou Giancarlo

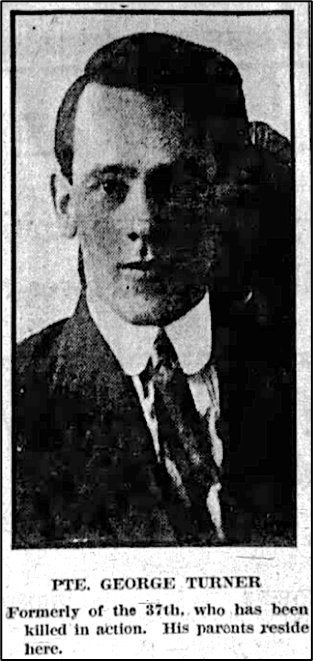

TURNER, George (#47966)

George Turner was 27 years old when he made the decision to serve his country. Only days later he was sent overseas, and within five months, he was on the front lines. Two months later, he was killed in action in Flanders Fields. His mother had his gravestone inscribed with an epitaph that professed her forever heartbreak.

George Turner was born in London, Ontario, on January 25, 1888, the son of Mrs. Mary Jane McCarthey of 232 Davis Street, Sarnia (later Mrs. Robert V. Harrison, of R.R. #1 Corunna, Ontario). [NOTE: In a couple of George Turner’s military records, his mother’s surname is recorded as McArthur.]

On May 31, 1915, George Turner, age 27, enlisted in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force (CEF) in Niagara Camp, Ontario. He stood five feet five-and-a-half inches tall, had dark brown eyes and dark hair, was single, and recorded his trade or calling as blacksmith, and his next-of-kin as his mother, Mrs. Mary Jane McCarthey, in Sarnia. George Turner became a member of the 37th Battalion, CEF.

Only days after enlisting, in early June 1915, George Turner embarked overseas from Montreal bound for the

United Kingdom aboard S.S. Hesperian. On June 20, 1915, in England, he was transferred to the 17th Reserve Battalion at Shorncliffe. Like all privates overseas, George earned his $1.00 + $0.10 (field allowance) per day.

In early September 1915, while on leave, George suffered an accident—while skating at a roller rink, he fell and injured his hip. The medical officer recorded that “Examination showed the hip in a very bad bruised condition & a large haematoma present.” George spent over two weeks in hospitals recovering from the injury—from September 6-11 at M.B.C.H., Shorncliffe, and from September 11-21 at Quex Park Military Hospital in Birchington, Kent.

Approximately six weeks later, on November 1, 1915, he was transferred and became a member of the 42nd Battalion, Quebec Regiment. That same day, he departed with the 42nd Battalion for France.

The 42nd Battalion had only arrived in Great Britain in mid-June 1915 and disembarked in France on October 9, 1915, one month before George Turner’s arrival. The 42nd Battalion fought as part of the 7th Canadian Brigade, 3rd Canadian Division.

On January 11, 1916, just over two months after arriving in France, Private George Turner of the 42nd Battalion was killed in action while fighting in Belgium. Shortly before eight o’clock that morning, the enemy opened up with their rifle grenades and fired 12 to 15 rounds on the Battalion’s trenches. The Canadians’ mortar battery responded by firing eight rounds at the enemy. After 25 minutes, the Germans resumed rifle grenade fire into the Battalion’s trenches, and once again the Canadians retaliated with their own battery fire. Over a 35-minute span, two men from the 42nd Battalion were killed (including George Turner) and 19 were wounded, four of them seriously.

George Turner’s death was recorded as O.C. Battalion Reports: Killed in Action, 11-1-16. His Commonwealth War Graves Register records him as Date of Death: 11-1-16. Killed in Action. Place of Burial: 50 yds, N of gate and 25 yards East of barn at R.E. Farm Cemetery near Wulverghem, Belgium. Sheet 28 – N.35.D.8.7. Cross erected.

His death, outside a formal, designated battle, was a common occurrence. In the daily exchange of hostilities—incessant artillery, snipers, mines, gas shells, trench raids, and random harassing fire—the carnage was routine and inescapable. High Command’s term for these losses was “wastage.”

The 42nd Battalion’s first Battle Honours awarded were not achieved until mid-1916—at Mount Sorrel (June 1916) and the Somme (July-November 1916).

In late January 1916, the telegraph company in Sarnia received the following telegram from the Adjutant-General in Ottawa:

Mrs. Mary Jane MacCarthur, Sarnia, Ont.

Deeply regret to inform you that No. 47966, Private George Tuner, of Sarnia, of 42nd formerly 37th Battalion, officially reported killed in action. Signed, Adjt.-Gen.

The telegraph company officials could not immediately deliver the telegram, as Mrs. Mary Jane MacArthur (George Turner’s mother and next of kin), was no longer residing in Sarnia. Shortly after, she was located in Hamilton, and the telegram was forwarded to her.

Following is a portion of the war diary of the 42nd Battalion for January 1916 that records the death of Private George Turner along with five other soldiers:

The efforts of the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade during three weeks in 1st Brigade area earned the following letter from Major Currie, C.B., Commanding 1st Canadian Division:

“It gives me a great deal of pleasure to inform you that during the stay of the 7th Infantry Brigade in the 1st Brigade area, they behaved at all times most gallantly. Besides, they did a great deal of very necessary and useful work.”

“At the time they took over the line, the trenches, owing to the very bad weather, were not in the best of shape but your fellows have made a great difference. I went over the line last Saturday morning and was delighted with what I saw had been done and so expressed myself to Brigadier General MacDonell. I asked him to convey my thanks to all the ranks of his Brigade: I know he will, but I want you to know as well how I have appreciated them. They were active in their patrolling, did a lot of wiring, greatly improved the front trenches, worked hard on supporting points and were aggressive always. While I deeply regret their casualties I do not think they were excessive.”

“Brigadier General Hughes has written me in warm terms of praise of what has been accomplished by MacDonell’s Brigade.”

7th Brigade total casualties during three weeks were 13 O.R killed, 2 Officers 69 O.R. wounded, of these 42nd Battalion total casualties were 3 O.R. killed (Ptes Matthews, E., Turner, G. and Ward G.) 39 O.R. wounded of whom 3 O.R. died of wounds (Ptes Wells, W.B., Belhumeur, J., McKillop, A.).

Following is a portion from the 42nd Canadian Infantry Battalion Official History. The book, written in 1931, is based on the official War Diary of the 42nd Battalion, Royal Highlanders of Canada, kept as part of their duty by the various Officers who served as Adjutant, together with reports of operations, correspondence files and other Orderly Room papers;

During the first week of January 1916 the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade first became responsible as a unit for the defence of a section of the British front line, taking over the area which had for some time been held by the 1st Canadian infantry Brigade. The 42nd Battalion went into divisional reserve on January 7th near Meteren and on January 8th took over the front line from the 3rd Canadian Battalion, Toronto Regiment.

Thus began a period of some two and a half months of the routine of trench warfare comprising as a rule, four days in the front line, four days in brigade reserve and four days in divisional reserve, then back to the front line…

The early part of the last day (7th) in billets was a busy one but the afternoon, as always on such occasions, seemed interminable. All extra equipment was packed away and there was nothing to do but wait. Each Company was detailed to relieve the corresponding company of the Battalion in the line. An advance party consisting of representatives of each Company and Headquarters moved off during the afternoon to take over trench stores and familiarize themselves with the position to be occupied by their Units. Shortly before dusk the “Fall in” was sounded and the Companies were finally inspected. A sharp command was given; then, in silence, except for the creaking of equipment, the Battalion moved off by platoons at intervals of fifty yards or so. At a given point guides were picked up and the Companies were led through more or less wet and winding communication trenches to their respective positions….

Finally the whole relief would be complete and all ranks would set about taking stock of their new quarters. Of the sentry groups one man would be standing in the fire step watching “no man’s land,” another would be sitting beside him and the others would be resting or working on trench repairs, each man taking his regular turn on sentry duty. Just before dawn and at dusk in the evening all ranks would “stand to” in case of enemy action. Following the morning “stand to” rum would be issued, tea would be made over braziers or tins of “canned heat” and all ranks would settle down for such rest as was possible during the day. Ration parties would go out at night to the nearest point to which the transport could bring rations and water and would carry them forward in sand bags. The mail, including parcels and newspapers, would be delivered daily with the rations and was looked forward to with a degree of eagerness that only those who were there can appreciate fully.

Such was the routine of trench warfare. This first tour of the 42nd was a quiet one with good weather. The only incident of note was an unfortunate experience with enemy rifle grenades on January 11th, two men being killed and nineteen wounded. The incident was reported as follows:–“Shorty before eight o’clock this morning the enemy opened rifle grenade fire of twelve or fifteen rifle rounds on trenches 14-A an 15-A. The Officer in charge of the latter asked O.C. Mortar Battery to reply, and eight rounds were fired with apparent effect, a breach being noticed in the front line German trench.

After an interval of about twenty-five minutes rifle grenade fire was resumed on our right sector. One fell outside dugout in the right of D-4 where the parapet is revetted with corrugated iron, which threw the charge into the dugout and the six men sleeping there were all wounded. The other men were wounded at various points along D-4 including some of the men carrying out the wounded at the top of communication trench D-4. In all, two men were killed and nineteen wounded, four of the latter seriously.

Owing to congestion of telephone line there was some delay in getting artillery retaliation. The battery responded promptly as soon as communication was obtained, and only two or three rifle grenades were fired after the battery opened.

Our rifle grenadiers fired about seventy rounds. The enemy’s fire activity extended over a period of about thirty-five minutes including the lapse of about twenty-five minutes referred to.”

Following is a brief story from a local newspaper reporting on Turner’s death:

SARNIA MAN KILLED

SARNIA, Jan. 22—It was officially announced this morning from military headquarters at Ottawa that Pte. Geo. Turner, son of Mrs. M.J. McCarthy, here, was killed in action on January 11.

Turner left this city to join the ranks at Sault Ste. Marie and had his military training at Niagara-on-the-lake in the 37th battalion, but left in June last with reinforcements for the front and was transferred to the 42 Battalion, in which he met his death.

In May 1921, George’s mother, then Mrs. Robert V. Harrison of Froomfield, received the Mother’s Cross in memory of her son who had been killed in action on the battlefield of Flanders. She also received the Mons Star and Military Medal from the war office.

George Turner, 27, is buried in R.E. Farm Cemetery, Heuvelland, Belgium, Grave III.A.12. On his headstone are inscribed the words THE PLACE MADE VACANT IN OUR HOME CAN NEVER MORE BE FILLED MOTHER.

Source: The Sarnia War Remembrance Project by Tom Slater

Editors: Tom St. Amand and Lou Giancarlo

VALLIS, Clifford George (#264281)

Born in England, Clifford Vallis immigrated to Canada at the age of 17. Six years later when he made the decision to serve his country, he was living with and helping to support his widowed mother in Sarnia. By the time he arrived in England five months later, he was already suffering from illness. Three months later he was returned to Canada where he never fully recovered. The illness ultimately took his life.

Clifford George Vallis was born in Pimlico, London, England, on March 10, 1893, the eldest son of William George and Kate (nee Fanner) Vallis. On April 3, 1892, 28-year-old William Vallis (born March 1864, Worcester Park, Surrey, England) married 26-year-old Kate Fanner (born September 1866, Stepney, Surrey, England) in St. Michael and All Angels, Bedford Park Hounslow, England. William and Kate were blessed with two children together: Clifford George (born 1893) and Herbert William (born February 24, 1897 in Pimlico, England). In April 1897, four-year-old Clifford started school at Holy Trinity School in Westminster. In 1901, the Vallis family—parents William (a coachman) and Kate Vallis, along with eight-year-old Clifford, and four-year-old Herbert, were residing in the county of Kensington, Brompton Ward, in London, England.

In September 1910, 17-year-old Clifford Vallis immigrated to Canada from London, England. He arrived aboard the passenger ship Lake Erie at the Port of Quebec on September 29, 1910, with his stated destination as Toronto, Ontario. In early 1911, his parents William (a motor car washer) and Kate, along with their 14-year-old son Herbert, were still residing in London, England.

Later that year, Clifford’s 44-year-old mother Kate, and his younger brother, Herbert, immigrated to Canada. They arrived in Montreal aboard the Grampian on May 8, 1911. Initially, Kate and her two sons resided in Toronto where they lodged with George and Esther McBride. Cliffords’ occupation was recorded as an inspector in a department store, and Herbert’s occupation was a clerk in a wholesale store. William Vallis arrived in Canada in July 1911 to join his wife and sons. Unfortunately, on March 5, 1912, William, the patriarch of the family, passed away from pneumonia in Toronto at age of 48.

Twenty-three-year-old Clifford Vallis enlisted in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force (CEF) on July 17, 1916, in Sarnia and Camp Borden. He stood five feet nine-and-three-quarter inches tall, had grey eyes and brown hair, was single, and lived at home with his mother Kate at the time, at 253 Devine Street, Sarnia. Clifford recorded his trade or calling as shipping clerk (he was employed with Mueller Mfg. Company), and his next-of-kin as his widowed mother, Kate Vallis on Devine Street. At the time, Clifford was helping to support his mother by giving her $40.00 a month. Clifford also recorded that he had prior military experience, having served four years (1910-1913) with the Queens Own Rifles, Toronto.

Clifford became a member of the Canadian Infantry, 213th Battalion, Eastern Ontario Regiment, CEF. Three months after enlisting, on October 17, 1916, he was transferred to the 173rd Battalion, Canadian Highlanders, CEF, with the rank of private. Just over three weeks later, on November 10, 1916, Clifford was admitted to the Sussex Military Hospital in New Brunswick and was diagnosed with nephritis. He was given treatment and remained in hospital for five weeks. After recovering, and five months after enlisting, Clifford embarked overseas in mid-December 1916, bound for the United Kingdom to join his battalion. The previous month, on November 14, the 173rd Battalion had embarked overseas from Halifax aboard S.S. Olympic.

On December 28, 1916 in England, Private Clifford Vallis was transferred to the 40th (Reserve) Battalion, Canadian Infantry. Less than two weeks later, on January 7, 1917, he was admitted to Moore Barracks Canadian Hospital, Shorncliffe, diagnosed again with nephritis. While in hospital, he was made a member of the 40th Reserve Battalion. At Moore Barracks Hospital, his Medical Case Sheet recorded that Clifford had influenza and rheumatism last winter, and was laid up for two and a half months in Toronto. His first attack of nephritis followed immediately. Second attack developed in Sussex, New Brunswick, 10-11-16. He was treated in St. John N.B. for five weeks. This the third attack commenced four days ago. First he noticed his face swollen, weakness and headache with some backache followed.

On February 10, 1917, Clifford was reported as much improved but will not be fit for service being boarded for discharge to Canada. He was discharged from Moore Barracks Hospital on March 12, 1917, with his diagnosis changed to “nephritis chronic”. The next day, he sailed from Liverpool on the hospital ship Letitia, returning to Canada for discharge.

The next month, on April 15, 1917, at the Discharge Depot in Quebec, Private Clifford Vallis was “Struck off Strength” from the 213th Battalion, discharged as “medically unfit”. Less than four weeks later, on May 10, 1917, Clifford was re-attested and taken on with the 213th Battalion in London, Ontario for further medical treatment. On that day, he was admitted to the Military Hospitals Commission of Canada (MHCC) at Wolseley Barracks in London.

Seven months later, on December 20, 1917, at 1:15 p.m., Private Clifford Vallis lost his life at Wolseley

Barracks Hospital in London, Ontario. The cause of death was recorded as nephritis and Vincent angina (infection of the pharynx). Clifford’s Canada War Graves Register records him as Date of Death: 20-12-17. London, Ontario Military Hospital. Nephritis – Discharge at Quebec, 15-4-17 but re-attested with M.H.C.C. for further medical treatment May 10th, 1917. Given every care and attention.

Kate Vallis later received a War Service Gratuity of $180.00 for the loss of her son Clifford. In 1921, she moved to Greenwood Avenue, Toronto. On December 28, 1920, Clifford’s 23-year-old brother, Herbert, married 22-year-old Mary Annie Phillips (born Watford, Ontario) at St. John’s Church in Sarnia, Ontario.

Clifford Vallis, 24, is buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, London, Ontario, Plot Section X.R.1. Originally, a wooden cross was erected over Clifford Vallis’ grave with all the particulars. The wooden cross was later replaced by a headstone. On his headstone are inscribed the words, AT REST. On the Sarnia cenotaph, his name is inscribed as H. Wallis.

Source: The Sarnia War Remembrance Project by Tom Slater

Editors: Tom St. Amand and Lou Giancarlo

WADE, Robert (#124061)

Born in England, Robert Wade along with his brother, immigrated to Canada in their early twenties and came to live and work in Sarnia. Other Wade family members followed, and three of the Wade boys would enlist in Sarnia in the same year. In fact, the three Wade boys fought together in one of the most horrific battles of the war. All three were wounded only days apart, but Robert’s wounds proved to be fatal.

Robert Wade was born in Boroughbridge, Yorkshire, England, on August 24, 1890, the son of William Alfred and Mary Ann (nee Robshaw-Burkhill) Wade, of Yorkshire, England. William Wade (born 1861) married Mary Ann Robshaw-Burkhill (born 1865) in December 1886, in Yorkshire. William and Mary Ann were blessed with nine children together: Sarah Ann (born 1887); John William (born 1888); Annie Elizabeth (born 1889); Robert (born 1890); Alfred (born July 25, 1893); Walter (born April 19, 1895); Herbert (born 1896); Emily (born 1898); and Hetty (born 1906).

In 1891, the Wade family was residing in Humberton, Yorkshire. The family comprised parents William (an agricultural worker) and Mary Ann, along with their children: Sarah Ann, John William, Annie Elizabeth and infant Robert Wade. Ten years later, in 1901, the Wade family was residing in Harrogate, Yorkshire, where William supported Mary Ann and his children by being a waggoner at a corn mill. Living with their parents were Sarah (age 14), Annie (age 11), Alfred (age 7), Walter (age 5), Herbert (age 4) and Emily (age 2). In 1911, some of the Wade family were still residing together in Yorkshire. By then, William worked as a hay cutter, and Mary Ann looked after the house and the children: 15-year-old Walter (an apprentice boot maker); 12-year-old Emily; and 5-year-old Hetty, who were both still in school.

Two of the Wade boys immigrated to Canada in 1911: 21-year-old Robert and 23-year-old John departed Liverpool, England, aboard S.S. Corsican. They arrived in Halifax on March 30, 1911, with $70 between them. Their intended destination was Sarnia to work as farm labourers. Other members of the Wade family would follow, and they resided at 301 Cameron Street in Sarnia.

In the 1914 Sarnia Directory, residing at 301 Cameron Street, were father William (labourer), sons Alfred (Broderick & Co.), and Robert (W.J. McIntyre) Wade. In the 1917-18 Sarnia Directory, residing at 301 Cameron Street, were William, Alfred (a soldier), and Walter (a soldier) Wade.

Three of the Wade boys served in the Great War. All three of them enlisted in the same year, and all three of them fought and were wounded in the same battle, only days apart.

Twenty-two-year-old Alfred (#402867) was the first to enlist, signing up with the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force (CEF) on January 29, 1915, in Sarnia. He stood five feet eleven inches tall, had blue eyes and fair hair, was single, and recorded his trade or calling as a clerk (later changed to tailor’s cutter – apprentice), and his next of kin as his father, William, at 301 Cameron Street, Sarnia. He became a member of the 34th Battalion and arrived in England on June 30, 1915, and was transferred to the 11th Reserve Battalion. On August 3, 1915, he was transferred to the 1st Battalion, and arrived with that unit in France the next day.

After serving for more than a year in France, on September 3, 1916, Private Alfred Wade was wounded in action—a gunshot wound to the thumb—during the Battle of the Somme. He was treated in several hospitals in France including at Boulogne, Etaples, and Havre, before being returned to Moore Barracks Canadian Hospital in Shorncliffe, England, on October 14, 1916. Suffering from frequent colds, cough, and steady loss of weight for

months, he was also treated for “bronchitis” while there. His condition was later diagnosed as pulmonary tuberculosis, the result of his time in the trenches.

In late December 1916, he was moved to Hastings Sanatorium Hospital. In mid-January 1917, he was invalided to Canada, sailing from Liverpool because of his “general debility”. In Canada, he entered Queen Alexandra Sanatorium in Byron for treatment. He was discharged on November 30, 1917, in London, Ontario “being no longer physically fit for war service”. He returned to his parents’ home on Cameron Street in Sarnia. Alfred Wade passed away on August 18, 1958, at the age of 65.

Twenty-year-old Walter (#90886) was the second Wade to enlist, doing so five months after his older brother Alfred. Initially signing up with the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force (CEF) on June 24, 1915, he became a member of the 29th Battery, Canadian Field Artillery, 1st Howitzer Brigade. One month later, on July 20, 1915, he was transferred to the 34th Battalion. One month after that, on August 30, 1915, Walter completed another CEF Attestation Paper in Sarnia, becoming a member of the 70th Battalion (#123033). Walter stood five feet five-and-a-half inches tall, had brown eyes and brown hair, was single, and recorded his trade or calling as a butcher, and his next of kin as his mother, Mary Ann Wade on Cameron Street, Sarnia.

In late December 1915-early January 1916, Walter was in a London, Ontario, hospital for a week due to bronchitis. Back in 1908, Walter had had pneumonia and was ill for six months. He recovered from this bout of pneumonia, but his bronchitis had persisted ever since.

On April 26, 1916, Walter embarked from Canada bound for the United Kingdom aboard S.S. Lapland. He arrived in England on May 5 (with his brother Robert) and became a private with the 70th Battalion. Less than two months later, on June 28, 1916, Private Walter Wade was transferred to the 24th Battalion and arrived the next day with that unit in the field in France (he arrived with his older brother Robert, who was in the same battalion). Soon after arriving in France, Walter experienced increased coughing and shortness of breath. His expectorations got worse, and he lost weight. He reported sick at LeHavre, and was put under treatment by his Medical Officer.

Despite his ill-health, Walter soon found his way to the front. On September 12, 1916, Private Walter Wade was wounded in action, hit on his abdomen by a piece of shell that knocked him over during the Battle of the Somme. His brother, Alfred, had been wounded only nine days earlier in the same battle. Walter was laid out for about two hours, and was taken to a dressing station and then to a field ambulance about six hours after being hit. On September 19, he was assigned to a rest camp and the next day was sent to 16th General Hospital at LeTreport. For almost three weeks, he vomited some blood and vomited after every meal. He was moved to other hospitals for treatment in France before returning to England. In England, he convalesced at Graylingwell War Hospital, Chichester (Oct. 11-23), and Canadian Convalescent Hospital, Epsom (Oct. 23-Dec. 13).

In mid-December 1916, he was in Moore Barracks Military Hospital, Shorncliffe, diagnosed with bronchitis. One week later, he was moved to Ontario Military Hospital, Orpington, Kent, where his symptoms of coughing and expectoration, shortness of breath, and loss of weight persisted. He was diagnosed with the disability “tubercle of lung” and was eventually discharged from hospital on April 11, 1916. On May 3, 1916, he was invalided to Canada for further medical treatment. At Spadina Military Hospital in Toronto, he was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis. Walter Wade was discharged from the military on August 31, 1917, in Toronto, declared as “medically unfit for war service”, and returned to Sarnia.

On March 31, 1914, 23-year-old Robert Wade (a clerk) married 23-year-old Vanny Louisa Twiner in Sarnia. Robert’s brother, Alfred, and his sister, Emily (of 301 Cameron Street), were the witnesses on the Marriage Certificate. (Alfred would be the first Wade boy to enlist in January 1915). Vanny Louisa Twiner was the daughter of Joseph (a farmer) and Elizabeth (nee Pash) Twiner. Robert and Vanny resided at 317 Maxwell Street, Sarnia.

Approximately 1 ½ years after getting married, 25-year-old Robert enlisted in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force (CEF) on October 8, 1915, in Sarnia. His two younger brothers had already enlisted in that same year: Alfred in January, and Walter in June 1915. Robert stood five feet five-and-a-half inches tall, had blue eyes and brown hair, and recorded his trade or calling as grocer’s clerk, and his next-of-kin as his wife, Vanny Wade of 317 Maxwell Street. Robert became a member of the 70th Overseas Battalion, CEF.

Six months after enlisting, on April 24, 1916, Private Robert Wade embarked overseas from Halifax bound for the United Kingdom aboard S.S. Lapland, arriving in England on May 5, 1916 (with his brother Walter). Two months later, on June 28, 1916, he was transferred to the Canadian Infantry, 24th Battalion, Quebec Regiment, at Shorncliffe. The next day, June 29, 1916, Private Robert Wade crossed the Channel and moved with the 24th Battalion to the front in France. His younger brother Walter, also with the 24th Battalion, arrived in France with him. Their brother Alfred had arrived in France with the 1st Battalion ten months earlier.

The three Wade brothers were soon engulfed in the horrendous mass butchery of one of the most gruesome battles of the war—the Battle of the Somme. Waged from July 1-November 18, 1916, it was one of the most futile and bloody battles in history. The Somme, a battle of attrition, lasted for more than four brutal months and saw the Allies advance around 10 kilometers. A more telling statistic is the number of injuries and deaths: of the 85,000 Canadian Corps, there were more than 24,000 Canadian casualties.

Incredibly, all three Wade brothers were wounded in a two-week period at the Somme in September 1916, one fatally. On September 3, Private Alfred Wade was wounded in action, hit in the hand by enemy gunfire. Nine days later, on September 12, Private Walter Wade was wounded in action, hit in the abdomen by a piece of enemy shellfire.

The second major offensive of the Somme battle was the week-long Battle of Flers-Courcelette (September 15-22). It was here where tanks made their first appearance in the war. The Battle was a stunning success for the Canadians, but it came at a cost of over 7,200 casualties. It was during this second major offensive of the Somme battle where Robert Wade was killed in action.

On September 16, 1916, four days after his brother Walter had been wounded, Private Robert Wade of the 24th Battalion, was killed in action on the battlefield during the Battle of Flers-Courcelette. In his Personnel File, there are five entries recorded in sequence: Reported from base wounded Sept. 16th, 1916 – shell shock; Reported wounded Inquires have been made; Previously reported wounded now missing since Sept. 16th, 1916; Previously reported missing now for official purposes presumed to have died on or since Sept. 16th 1916; and Previously reported missing presumed dead now reported killed in action Sept. 16, 1916.

Robert Wade’s Commonwealth War Graves Register records him as Date of Death on or since: 16-9-16. Previously reported Missing now for Official purposes presumed to have died – now Killed in Action. At some point, Robert’s remains were exhumed from the original place of burial, and then reburied in Adanac Military Cemetery, 6 ¼ miles North East of Albert.

His widow, Vanny Wade, received a War Service Gratuity of $180.00 for the loss of her husband. She resided at 128 Essex Street, Sarnia, for a time, and later moved to Water Lane, Selsley, Nr. Stroud, Gloucester, England.

Robert Wade, 26, is buried in Adanac Military Cemetery, Miraumont, Somme, France, Grave II.B.2.

Source: The Sarnia War Remembrance Project by Tom Slater

Editors: Tom St. Amand and Lou Giancarlo

WALTERS, Joseph John

Sarnia-born Joseph John Walters, an only child, was 21 years old in April 1916 when he made the decision to serve his country. Within six months, he was a lieutenant taking part in one of the most savage and horrifying battles in history. Joseph survived this formidable battle, but the following spring he was killed in action while fighting to rid France of its German oppressors.

Joseph Walters was born in Sarnia, Ontario, on September 26, 1894, the only child of Jacob D. and Anna K. (neé Peiffer) Walters. In 1901, the Walters family was residing in London, Ontario—parents Jacob (born April 14, 1866, occupation recorded as “traveller”) and Anna Walters (born January 8, 1870, in Nova Scotia); their six-year-old son Joseph John; and a 12-year-old cousin, Mabel Peiffer (born in Nova Scotia).

Ten years later, in 1911, the Walters London household included parents Jacob, 44, and Anna, 40, along with their 15-year-old son Joseph.

Note: In the 1901 Census, the Walters family is recorded as having German origin. In the 1911 Census, the family is recorded as having Scottish origin.

On April 22, 1916, Joseph Walters, age 21, completed his Officers’ Declaration Paper with the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force and received his medical approval in St. Thomas, Ontario. He stood five feet six inches tall and lived at home with his parents at 1029 Richmond Street in London, Ontario, at the time. He recorded his occupation as journalist (“reporter newspaper”), and his next-of-kin as his mother, Mrs. J.D. Walters, of 1029 Richmond Street. He also recorded that he had prior active militia experience with the 25th Elgin Regiment, St. Thomas, Ontario, and that he had several years’ military service in the cadets.

Joseph became a member of the 91st Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force, with the rank of lieutenant. Prior to departing for overseas, his former newspaper employer, under the headline “ADVERTISER “BOYS” WHO LEAVE WITH 91ST” reported that When the 91st (Elgin County) Battalion leaves for overseas, which will be almost at once, two former members of the reportorial staff of The Advertiser go with it as subalterns. Lieut. Joe Walters, platoon commander, and Lieut. Clyde Kennedy, signalling officer. Both were on the local staff for some time, Lieut. Walters having been a member for several years, and was night city editor at the time he resigned to take the officers’ training course. Both officers were popular with their fellow members of the staff, and their departure will be regretted. The good wishes of every employee of The Advertiser goes with its two representatives in the 91st.

Joseph Walters embarked overseas from Halifax bound for the United Kingdom aboard S.S. Olympic on June 28, 1916. He arrived in Liverpool on July 5, 1916.

On July 15, 1916, Lieutenant Joseph Walters was transferred to the 35th Battalion at West Sandling. Seven weeks later, on September 7, he earned qualifications in a “bombing course, C.M.S.”. Later that month, on September 29, he was transferred to the Canadian Infantry 20th Battalion, Central Ontario Regiment and then embarked across the English Channel to the front lines in France.

The 20th Battalion had been formed with volunteers from militia regiments across Central Ontario and began arriving in France in mid-September 1915, where it fought as part of the 4th Canadian Brigade, 2nd Canadian Division. On arrival, the Battalion was given a section of the front on the Ypres Salient, near Messines. To hold the line, soldiers faced nightly patrolling in no man’s land, endless repairs to wire and trenches, and continual shelling. The winter of 1915-16 was spent in a routine of 18 days on the front and 6 days in the rear, all while battling lice, trench foot, and disease. In March 1916, steel helmets were issued to all ranks.

The 20th Battalion was awarded their first Battle Honour at Mount Sorrel in June 1916. Over the two weeks of fighting at Mount Sorrel that resulted in almost no change in the ground held by both sides, the “June Show,” as the battle was known, came at a cost of 8,700+ killed, wounded, or missing Canadians.

Lieutenant Walters and the 20th Battalion was soon after thrust into the horrendous mass butchery that was the Battle of the Somme. Waged from July 1 to November 18, 1916, it was one of the bloodiest and most futile battles in history. The Somme, a battle of attrition, lasted for more than four brutal months and saw the Allies advance around 10 kilometers. A more telling statistic is the number of injuries and deaths: of the 85,000 Canadian Corps, there were more than 24,000 Canadian casualties. Joseph Walters was fortunate enough to survive this harrowing experience.

In the New Year, on January 21, 1917, Joseph was granted 10 days leave, and he returned to England. He returned to the field in France on February 4, 1917. A month and a half later, he was admitted to No. 22 Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) as a result of P.U.O. (pyrexia – of unknown origin fever of an undetermined cause). One week later, on March 31, 1917, he was admitted to Duchess of Westminster’s Hospital at Le Touquet, France, diagnosed with P.U.O. slt. He remained there for one week and was discharged to Details Camp Etaples on April 6, 1917.

The 20th Battalion fought at the Battle of Vimy Ridge (April 9-12, 1917), which was the first time (and the last time in the war) that all four divisions of the Canadian Corps, with soldiers from every region in the country, would surge forward simultaneously. Of the 97,000 Canadians who fought and achieved victory at Vimy Ridge, approximately 7,004 were wounded and 3,598 were killed in four days of battle.

On April 14, 1917, two days after the Battle of Vimy Ridge, Lieutenant Joseph Walters returned to the field where he rejoined his unit, the 20th Battalion.

On the night of May 10, 1917, less than one month after returning to his unit, Lieutenant Joseph Walters was killed in action by enemy shellfire in the area of Vimy Ridge. The following excerpt is from The History of The Twentieth Canadian Battalion, CEF, In The Great War, 1914-1918 by Major D.J. Corrigall, D.S.O., M.C., 1935:

From the railway embankment east of Vimy Ridge to the forward area was a long communication trench called “C.P.R. Trench”, which ended at a trench running from Arleux to Acheville, known as “The Arleux Loop”. The sunken roads already mentioned were named “Vancouver”, “Saskatchewan”, “Manitoba”, “Winnipeg” and “Alberta” roads. “Vancouver” was half way from the railway embankment to the Arleux Loop. “Saskatchewan” crossed at the junction of C.P.R. Trench and Arleux Loop. The others cut across the “Loop” at five hundred yards intervals from thence to the front line….

During the early hours of May 10, “B” and “D” Companies, 20th, were relieved by “A” and “B” Companies, 21st Battalion, as supports to the 18th Battalion. On relief, “B” and “D” Companies, 20th, relieved the 19th Battalion in Winnipeg Road, the former occupying the part south of, and the latter the part north of, Arleux Loop.

Nothing unusual occurred during the day, but at 7:30 p.m. the enemy shelled our area for forty-five minutes, particularly Winnipeg Road, “D” Company’s position. Their casualties were very heavy, three officers killed, Lieuts. Ardagh, Walters, and Hannaford, one wounded, Lieut. Torrance, nine other ranks killed and thirty-two wounded. The casualties in the other companies were slight. During the night “D” Company, under Major L.H. Bertram, moved up to attack from Alberta Road. We were then ordered to consolidate these positions and spent the nights of May 11 and 12 digging and wiring. Burial parties were also detailed and the area east of Manitoba Road was cleared by the morning of the 13th. Our casualties since the 8th had been one hundred and thirty-two.

On May 19, 1917 in Rouen, France, the Officer in Command of the 20th Battalion recorded on the Field Service Record that Lieutenant J.J. Walters was “Killed in Action, In the Field (France), 10-5-17”. Joseph Walters’ Commonwealth War Graves Register records the following: Date of Death: 10-5-17. Killed in Action.

His death, outside a formal, designated battle, was a common occurrence. In the daily exchange of hostilities—incessant artillery, snipers, mines, gas shells, trench raids, and random harassing fire—the carnage was routine and inescapable. High Command’s term for these losses was “wastage.”

Joseph Walters remains were originally buried in Acheville Road Cemetery and were later exhumed and reburied in Lievin Communal Cemetery, 2 miles W.S.W. of Lens. Not long after Joseph’s death, his parents Jacob and Anna Walters were residing in Clover House, Rochester, New York, U.S.A.

Joseph Walters, 22, is buried in Lievin Communal Cemetery Extension, Pas de Calais, France, Grave III.A.16.

His name was not originally on the Sarnia cenotaph, unveiled in November 1921. In November 2019, his name, along with 25 others, was added to the Sarnia cenotaph, engraved in stone to be remembered always.

Source: The Sarnia War Remembrance Project by Tom Slater

Editors: Tom St. Amand and Lou Giancarlo

WATSON, Edward Phillip (#3131744)

American-born Edward Watson was living in Sarnia with his parents and only brother when he was drafted for military service. Seven months after being called to service, he was fighting in the last great and costly campaign of the war. He was killed in action five weeks before the Great War ended. His parents commemorated his sacrifice locally in Lakeview Cemetery and Parker Street United Church.

Edward Phillip Watson was born in Flint, Genesee County, Michigan, USA, on July 8, 1895, the youngest son of Edward Proctor Watson Sr. and Ella (nee Barron) Watson. On January 21, 1893, 23-year-old tinsmith Edward Sr. (born May 29, 1869 in Sarnia) married 20-year-old Ella Barron (born February 26, 1872 in Sarnia) in Port Huron, Michigan. Both Edward Sr. and Ella were residing in Sarnia at the time. Edward Sr. and Ella were blessed with two children: Harold Barron, born March 24, 1893, and Edward Phillip Jr., born 1895. Though parents Edward Sr. and Ella were both born in Sarnia, their two sons were both born in the USA.

In 1901, the Watson family in Sarnia included parents Edward Sr. (age 31) and Ella (age 28), and their two boys: eight-year-old Harold and five-year-old Edward Jr. Father Edward Sr. supported his family by working as a tinsmith at the time. Ten years later, in 1911, the Watson family was residing at 147 Watson Street, Sarnia. Ella was a homemaker; Edward Sr. was employed as a tinsmith at Goodisons, and their two teenage sons were working as well: Harold, 17, was a book seller and Edward Jr., 15, was an express clerk.

As the war dragged on in Europe, with the Canadian troops thinning at an alarming rate, and no end to the war in sight, the government instituted the Military Service Act (MSA) in July 1917.

Twenty-two-year-old Edward Jr. was drafted under the Military Service Act of 1917, Class One. He underwent his medical examination in Sarnia, on November 6, 1917, and was called to service on January 9, 1918, reporting to the 1st Depot Battalion, Western Ontario Regiment in London, Ontario. He stood five feet ten-and-three-quarter-inches tall, had grey eyes and dark brown hair, was single, and lived at home with his parents on Watson Street at the time. He recorded his trade or calling as hammer operator and his next-of-kin as his father, Edward Sr. of Watson Street, Sarnia.

On February 21, 1918, Edward Jr. embarked overseas from Halifax bound for the United Kingdom aboard S.S. Cretic. He arrived in England on March 4, 1918, and the next day, was taken on strength into the 4th Canadian Reserve Battalion at Bramshott.

Five months later, on August 18, 1918, Private Edward Watson Jr. proceeded from Camp Witley bound for France, where he became a member of the Canadian Infantry, 1st Battalion, Western Ontario Regiment. He arrived at the Canadian Base Depot in France on August 20 and arrived three days later at the Canadian Corps Reinforcement Camp (CCRC). Twelve days later, on September 1, 1918, Edward Watson joined the 1st Battalion in the field at the Front.

Approximately 125,000 men were conscripted into the CEF, and only 48,000 were sent overseas. The first conscripts went to France in April 1918. That summer, thousands more of them, mostly infantry, were funnelled across the English Channel to Canadian Corps reinforcement camps in France. Only about 24,000 Canadian MSA conscripts reached the Western Front lines. They helped keep the ranks of the ragged infantry battalions at or near full strength during the crucial final months of the war, thus allowing the Canadian Corps to continue fighting in a series of battles.

Early in the summer of 1918, Allied Commanders proposed a plan to take advantage of German disarray following their failed Spring Offensive. Canadian troops were to play a key role as “shock troops” in cracking the German defences. They spent two months preparing for what became their final great campaign of the war.

On arriving at the front in France, Private Edward Watson Jr. was soon embroiled in this pivotal campaign, one that featured intense and brutal fighting as the end of the war neared. The Hundred Days Campaign (August 8 – November 11, 1918, in France and Belgium) was the “beginning of the end” of the Great War. Canadians were called on again and again over the three-month period to lead the offensives against the toughest German defences. The series of victories repeatedly drove the Germans back, culminating in Germany’s unconditional surrender on November 11, but it came at a high price: approximately 46,000 Canadians were killed, wounded, or missing.

The first offensive in the Campaign was the Battle of Amiens in France (August 8-14, 1918), a truly all-arms battle, one in which all four Canadian divisions were involved. Over the course of one week, in a battle that British Field Marshal Douglas Haig called “the finest operation of the war”, the Canadians would advance nearly 14 kms—but it came at a cost of 11,822 Canadian casualties.

The second offensive in the Campaign was the Battle of Arras and Breaking the DQ Line in France (August 26-September 3, 1918), where Canadians were part of a spearhead force tasked with crashing one of the most heavily fortified positions, the Hindenburg Line—a series of strong defensive trenches and fortified villages. General Sir Julian Byng called the Canadian victory at the 2nd Battle of Arras and breaking of the DQ Line “the turning point of the campaign”, but it came at a cost of 11,400 Canadian casualties.

The third offensive in Canada’s Hundred Days Campaign was the Battle of Canal-du-Nord and Cambrai in France(September 27-October 11, 1918). Against seemingly impossible odds and a desperate and fully prepared enemy, the Canadians fought for two weeks in a series of brutal engagements. They successfully channelled through a narrow gap in the canal, punched through a series of fortified villages and deep interlocking trenches, and captured Bourlon Wood and the city of Cambrai. General Arthur Currie would call it “some of the bitterest fighting we have experienced” and it came at a cost of 14,000 Canadian casualties. Private Edward Watson Jr. of the 1st Battalion lost his life during this third offensive in France.

On October 1, 1918, exactly one month after arriving at the front, Edward was killed in action. His loss was originally recorded as Reported missing after action October 1st, 1918. In mid-October 1918, his parents Edward Sr. and Ella in Sarnia received information from the War Office that their youngest son EDWARD WATSON, HAS BEEN OFFICIALLY REPORTED MISSING.

By the end of that month, Private Edward Watson Jr.’s death was officially recorded as Previously reported missing, now reported killed in action October 1st, 1918. His Commonwealth War Graves Register records the following: Date of Casualty: 1-10-18. Reported from Base Missing. Now Killed in Action. Buried Sancourt British Cemetery, 10 ¾ miles S.E. of Douai, France.

Approximately five weeks after Edward Watson’s death, the Great War came to an end.

Edward Watson Jr., 23, is buried in Sancourt British Cemetery, Nord, France, Grave I.C.5. In Lakeview Cemetery in Sarnia, there is a memorial grave marker in honour of Edward Watson. The marker reads IN MEMORY OF EDWARD PHILIP WATSON 1895-1918 PTE. 1ST BTN. W.O.R. FELL AT CAMBRAI OCT. 1, 1918 BURIED IN SANCOURT BRITISH CEMETERY FRANCE ‘FAITHFUL UNTO DEATH I WILL GIVE THEE A CROWN OF LIFE’.

On September 23, 1920, Edward Jr.’s 27-year-old brother, Harold Watson, married 32-year-old Alice Victoria Millard (born November 6, 1887 in Sarnia) in Sarnia. The following year, in 1921, parents Edward Sr. (a tinsmith with Imperial Oil) and Ella Watson, along with their son Harold (a meter reader) and his wife Alice, were residing together at 147 Watson Street, Sarnia.

Seven years later, in 1928, a stain glass memorial window was unveiled in Parker Street United Church in Sarnia to commemorate the sacrifice made by Private Edward Watson. The inscription at the base of the window reads In Loving Memory of Pte. E.P. Watson Killed in Action on Oct. 1, 1918. The window is still there today, in what is now called Lighthouse Community Church.

Edward Sr. and Ella Watson, along with their son, Harold, and his wife Alice, are all buried in Lakeview Cemetery in Sarnia.

Source: The Sarnia War Remembrance Project by Tom Slater

Editors: Tom St. Amand and Lou Giancarlo

WEATHERILL, Bertrand Peter (#123146)

Bertrand Peter Weatherill was 22 years old in September 1915 when he made the decision to serve his country. His older brother enlisted soon after and, together, they embarked overseas and arrived in France in the same battalion. Both brothers were soon fighting in one of the most atrocious battles of the war. Approximately one year after enlisting, Bertrand was killed in action on the Somme battlefield. The 23-year-old has no known grave, but is memorialized on the Vimy Memorial in France.

Bertrand Weatherill was born in Oil City, Lambton County, on November 8, 1892, the youngest child of Robert Weatherill Sr. and Laura Louisa (neé Keating) Weatherill. On June 22, 1887, 31-year-old Robert (born September 1854 in Toronto) married 23-year-old Laura (born September 12, 1863 in Oil Springs) in Oil City, Lambton, Ontario. Robert Sr. and Laura Weatherill were blessed with three children: Helen Eskelly Mitchell (born March 13, 1888); Robert Jr. James (born September 9, 1889); and Bertrand Peter (born 1892).

In 1891, the Weatherill family was residing in Enniskillen, Lambton East—parents Robert Sr. (a storekeeper) and Laura, along with their children Helen (age three) and Robert Jr. (age one). Robert Sr. was a merchant in Oil City before engaging in a brokerage business and later in fruit farming. Tragedy hit the Weatherill family eight years later when they lost 44-year-old Robert Sr. On September 20, 1899, the married father of three, passed away on his farm from the effects of septicemia (blood poisoning). Bertrand was not quite seven years old at the time.